NB Dance Reviews

A small audience, which included the great legend of Canadian dance, Frank Augustyn, was treated to an outstanding show in the BlackBox Studio Theatre (Saint John) on December 28, 2024.

A riveting remount of Georgia Rondos’ work Three Lights, depicted a mournfully nostalgic tribute to the age of sail. A series of historic photographs were the perfect backdrop for a masterful prose spoken by Seth O’Neill. The narrator powerfully iterated images of the versatile sea; daringly defining the cut of our coastline, creating calm for the footsteps of “the Carpenter’s son”, and even challenging the audience with a nonsensically circular perspective, questioning, “ARE YOU COMING, OR WHAT?”

The power of the spoken word was supported by a perfect soundscape, and matched by the perfectly expressive movement of the dancer, Kleis Rondos. As bride, mother, ship, or sea, Rondos captured the excitement and versatility as well as the soothingly repetitious monotony of the waves and currents.

The Three Lights‘ aural and visual poignancy was overlaid by Liam Caines’ masterful interpretation of sailor and highlighted by the character’s tender pas de deux with the memory of a beloved person, or era, who had obviously slipped away. Caines’ painfully loving caress, gentle gaze, soft release, and longing reach were tremendously impactful.

The work was a moving choreographic love letter to a distant time. And to answer the question…with deepest regret, it is doubtful we will return to such a level of connectedness with the sea and self.

The final chorus of sailor and beloved, joined by ocean-narrator, left the audience with a strong, hopeful final tableau.

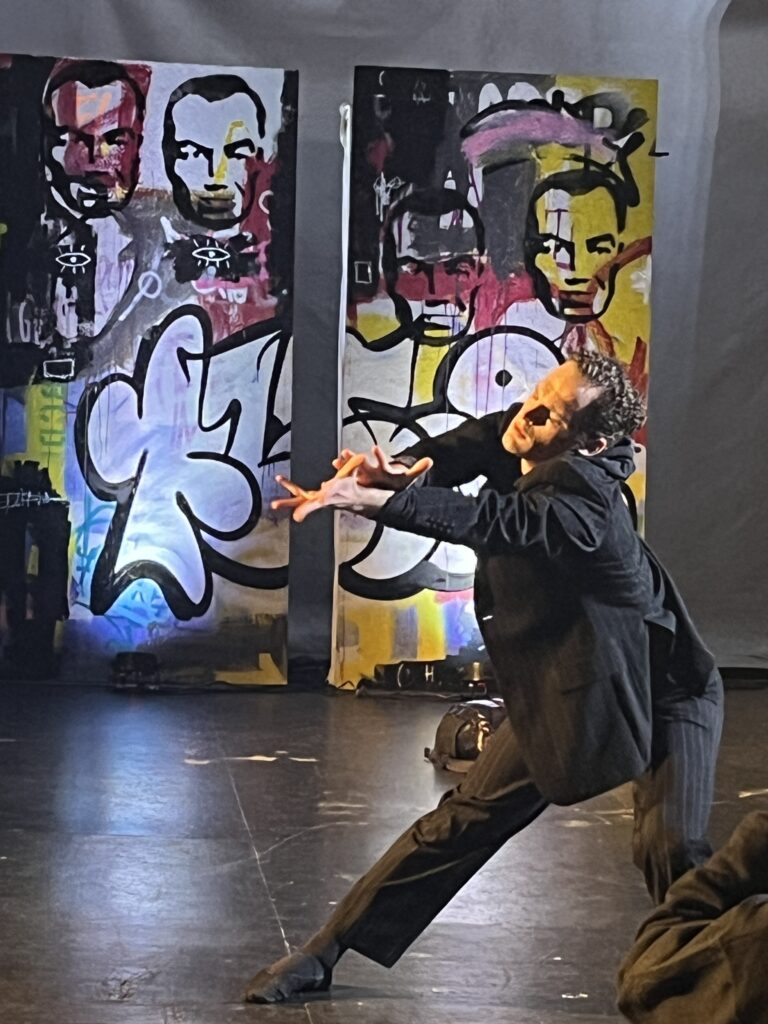

The second part of the show featured the premiere of a new Rondos work, Alone. With inflections of Rondos’ previous urban-inspired works, and subtle reminiscence of D’Andy, Alone was a flawless and relevant choreographic depiction of one’s struggle with personal demons.

Using authentic, uncontrived movement, effective gesture, and an array of intensity as her medium, made him simultaneously withdrawn from and connected to the audience; a dichotomous challenge echoed by the beautifully gritty graffiti art panels that served as the work’s magnificent backdrop, and the well-aligned interesting score.

As always, Rondos requires no tricks and no gimmicks-just a perfectly meted balance of thoughtful choreography articulated by highly capable dancers, and supported by minimal yet perfectly effective landscape and soundscape.

The audience was enthusiastically delighted, and to those who weren’t there…sorry you missed it.

Andrea Scott

Russ Hunt’s Reviews

The Kitchen

By Arnold Wesker

Theatre St. Thomas

March 1999

The Kitchen is unlike anything I’ve ever seen on a stage. Knowing a bit about the script beforehand, I thought it was pretty much impossible to stage: a cast of 27, most of whom are on stage most of the time — and not just standing around, either — and a million props. A whole large-restaurant kitchen, in fact, with all the counters and work spaces and pots and pans and utensils and stoves and ovens. All crammed into the Black Box acting space, with a couple of restaurant-style swinging doors at the back. And, as the evening swings into gear, a dozen waitresses bursting through with their orders, picking up the plates and steaming back out again, another dozen or so cooks and chefs plying their various trades with increasing speed and urgency, bus boys hustling back and forth, and the owner occasionally drifting ethereally through the whole chaos. Think Look Back in Anger crossed with Riverdance.

For the production, the funding TST received last year from “scholars.com” let them hire, to work with the students on the production, three professionals — Patrick Clarke, who supervised the incredible set, Tim Gorman, who supervised the professional and unobtrusive lighting, and, maybe most important, a choreographer, Georgia Rondos, who acted as assistant director and, I assume, worked on keeping all those folks moving without bumping into one another.

I’ve thought for years that the really strong suit at Theatre Saint Thomas has been ensemble — Ilkay’s produced some wonderfully coherent ensemble productions (Dancing at Lughnasa was one of them), but this is over the top. It’s almost as though there were nothing here but ensemble. In that sense it’s a lot like Riverdance without the Michael Flatley figure: you never know where to look exactly, but wherever you do look the person you look at is totally focused on the immediate task — slicing (invisible) cake, butchering an (invisible) pig, scooping (invisible) sauces out of pots onto plates. You have the feeling — I did, anyway — that I wasn’t actually choosing where to look, that the production was finely tuned enough that it was controlling where I actually put my eyes most of the time. It’s rather like the Stephen Bochco-style TV show (Hill Street Blues was the first one, but lots of them do it now), where the action is immersed in a fully-realized context, with hundreds of extras doing their thing in the background, and the foreground, and the camera telling you who to follow and the microphone picking up the voices. Only here there is no camera, and no microphone; it’s the direction, the blocking, the choreography, and the actors who have to make sure you know where the focus is.

If there’s a weakness in the production, that’s it: there were times, lots of them, when I missed dialogue because the actors seemed to be relying on the fact that they were pretty close to us — the Box isn’t all that big, after all — rather than projecting out to the back walls. So, particularly in the extremely hectic first act, I think I missed a good deal of what I might have focused on. Still, I always knew where the center of the action was: I think I’d have known had I been watching with earplugs, because the visual movement worked so clearly to tell me what I was to attend to.

And it’s not quite accurate to say this is Riverdance without Flatley: there is, in fact, a central figure in the play, and although he’s one of the crowd at the beginning, by the end of the first act we know that Peter, the German fish cook whose workspace is down front, is the linchpin on whom it’s all going to turn. He’s played extremely powerfully by Jef Bate Boerop, an actor I’ve admired in other productions here — most notably, Krapp’s Last Tape. Here, he’s playing a hair-trigger explosion about to occur, a tense, vibrant, aggressive, figure way too full of life for his own good. It’s clear that the center of the play is Peter’s relationship with the waitress Monique (Amy Chedore, whom I haven’t seen on stage before, and who is perfect as a sexy, flirtatious and unattainable love interest), and with other central characters like his countryman Hans, a cutlet cook (Sean Myles, playing a wonderfully innocent, ebullient ruddy-faced German who plays and sings a great, plaintive “Lily Marlene” during the “lull” at the beginning of the second act), the pastry chef, Paula (Katie MacLaurin, who was one of the narrators in Lovers, and who has an extremely solid, strong stage presence), and the new cook, an Irishman named Kevin (Jeff Richardson, who makes his character much more than the expository device he might have been).

As the play comes more and more to focus on Peter, and his bursts of joy and rage become more excessive, we come to see the main movement in the play as a kind of two-part crescendo, like a wonderful piece of music: Act I ends in full flight, with the kitchen flat out and everybody moving full tilt. Act II comes to almost the same climax, only this time it’s focused on the inevitable explosion around Peter, who’s alienated Monique and has finally reached the end of his rope.

What’s amazing is that the play also turns out to be chock full of ideas — for instance, a powerfully satiric take on a Britain which has an extremely difficult time making room for the “foreigners” who make up most of the staff in the kitchen — German, Italian, Spanish, Greek, French, Irish, a virtual European Common Market, with Max the butcher screaming that they’re all in England now so they should all speak English (if the play had been written in 1997 instead of 1957 they’d mostly be Middle Eastern and Asian, I’d think, but Max would be the same). Or a similarly satiric take on the traditional roles of men and women (almost all the cooks are men, and all the, um, waitpeople except, of course, the headwaiter, are women).

But finally the point is that amazing, tightly choreographed experience of a kitchen at full tilt. The closest thing I’ve seen to it wasn’t on a stage, it’s ER in crisis, or maybe *MASH* with the casualties incoming. An experience I’m sorry anybody has to miss.

A final note

I would normally not do this, but I think a reviewer who saw this production and wondered what the point of it was should quit going to theatre altogether. For a review which says that, click here.

Article on Rondos’ Choreography: Gwion Gwion, December 2015

The Bradshaw Foundation, Australia

https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/news/cave_art_paintings.php?id=Gwion-Gwion-rock-art-and-dance

Georgia Rondos Featured in artsnb Annual Report

Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s Annual Report 2012/13

GUEST TEACHERS

The Professional Division benefited tremendously from the teaching and guidance of many guest teachers this season.

Mark Godden visited the School as a guest choreographer in September 2012. In October 2012 and choreographer Georgia Rondos was in Winnipeg to work with some of the students in our Aspirant program. Ms Rondos created a new work entitled Gnossiennes, which was performed at On the Edge, the Aspirant Program year-end showcase, in May 2013.

While in Winnipeg to work with the Company in March 2013, Guest Ballet Master Jean- Yves Esquerre taught classes in the Ballet Academic and Aspirant programs. Professional Div ision Founding Director David Moroni, C.M., returned to Winnipeg from April 8 to May 3, 2013, to work with the senior ladies and men in the Ballet Academic Program. Former Artistic Director of Boston Ballet and international guest teacher Anna-Marie

Holmes was in Winnipeg to work with our students for two weeks in May 2013.

2013 GRADUATES

The 2013 Graduation Performance and Convocation took place on the afternoon of June 1, 2013.

International guest teacher and former Artistic Director of Boston Ballet Anna-Marie Holmes addressed the graduating class as the 2013 convocation guest speaker.

A celebratory dinner was held that evening at the St. Charles Country Club and attended by the graduates, their families and staff of the School.

RWB School would like to congratulate the followingandwishthemcontinuedsuccess in their future endeavours: Sarah Harris, Kira Hofmann, Julia Jones-Whitehead, Hunter Loewen, Jesse Petrie, Naomi Tanioka, Seth Buckley; and Teacher Training Program Graduates Denise Belzile, Catherine Devonshire, Yumi Ito, and Christine Wu.